Semitic languages

| Semitic | |

|---|---|

| Geographic distribution: |

Middle East, North Africa, Northeast Africa and Malta |

| Linguistic Classification: | Afro-Asiatic Semitic |

| Subdivisions: |

East Semitic (extinct)

West Semitic

South Semitic

|

| ISO 639-2 and 639-5: | sem |

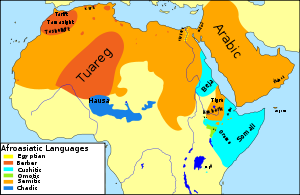

The Semitic languages are a group of related languages whose living representatives are spoken by more than 467 million people across much of the Middle East, North Africa and the Horn of Africa. They constitute a branch of the Afroasiatic language family. The most widely spoken Semitic language by far today is Arabic[1] (206 million native speakers).[2] It is followed by Amharic (27 million),[3][4] Tigrinya (5.8 million),[5] and Hebrew (about 5 million).[6]

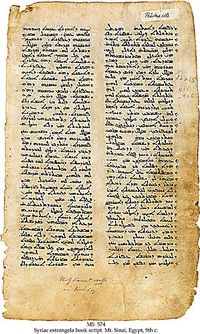

Semitic languages are attested in written form from a very early date, with texts in Eblaite and Akkadian appearing from around the middle of the third millennium BC, written in a script adapted from Sumerian cuneiform. The other scripts used to write Semitic languages are alphabetic. Among them are the Ugaritic, Phoenician, Aramaic, Hebrew, Syriac, Arabic, South Arabian, and Ge'ez alphabets. Maltese is the only Semitic language written in the Latin alphabet and the only official Semitic language of the European Union.

Contents |

History

Origins

The Semitic family is a member of the larger Afroasiatic family, all of whose other five or more branches are based in Africa. Largely for this reason, the ancestors of Proto-Semitic speakers are believed by many to have first arrived in the Middle East from Africa, possibly as part of the operation of the Saharan pump, around the late Neolithic.[7][8] Diakonoff sees Semitic originating between the Nile Delta and Canaan as the northernmost branch of Afroasiatic. Blench even wonders whether the highly divergent Gurage indicate an origin in Ethiopia (with the rest of Ethiopic Semitic a later back migration). However, an opposing theory is that Afroasiatic originated in the Middle East, and that Semitic is the only branch to have stayed put; this view is supported by apparent Sumerian and Caucasian loanwords in the African branches of Afroasiatic.[9] A recent bayesian analysis of alternative Semitic histories supports the latter possibility and identifies an origin of Semitic languages in the Levant around 5,750 BP with a single introduction from southern Arabia into Africa around 2,800 BP.[10]

In one interpretation, Proto-Semitic itself is assumed to have reached the Arabian Peninsula by approximately the 4th millennium BC, from which Semitic daughter languages continued to spread outwards. When written records began in the mid 3rd millennium BC, the Semitic-speaking Akkadians and Amorites were entering Mesopotamia from the deserts to the west, and were probably already present in places such as Ebla in Syria.

2nd millennium BC

By the beginning of the 2nd millennium BC, East Semitic languages dominated in Mesopotamia, while West Semitic languages were probably spoken from Syria to Yemen, although Old South Arabian is considered by most to be South Semitic and data are sparse. Akkadian had become the dominant literary language of the Fertile Crescent, using the cuneiform script which was adapted from the Sumerians, while the sparsely attested Eblaite disappeared with the city, and Amorite is attested only from proper names.

For the 2nd millennium, somewhat more data are available, thanks to the spread of an invention first used to capture the sounds of Semitic languages — the alphabet. Proto-Canaanite texts from around 1500 BC yield the first undisputed attestations of a West Semitic language (although earlier testimonies are possibly preserved in Middle Bronze Age alphabets), followed by the much more extensive Ugaritic tablets of northern Syria from around 1300 BC. Incursions of nomadic Aramaeans from the Syrian desert begin around this time. Akkadian continued to flourish, splitting into Babylonian and Assyrian dialects.

1st millennium BC

In the 1st millennium BC, the alphabet spread much further, giving us a picture not just of Canaanite but also of Aramaic, Old South Arabian, and early Ge'ez. During this period, the case system, once vigorous in Ugaritic, seems to have started decaying in Northwest Semitic. Phoenician colonies spread their Canaanite language throughout much of the Mediterranean, while its close relative Hebrew became the vehicle of a religious literature, the Torah and Tanakh, that would have global ramifications. However, as an ironic result of the Assyrian Empire's conquests, Aramaic became the lingua franca of the Fertile Crescent, gradually pushing Akkadian, Hebrew, Phoenician, and several other languages to extinction (although Hebrew remained in use as a liturgical language), and developing a substantial literature. Meanwhile, Ge'ez texts beginning in this era give the first direct record of Ethiopian Semitic languages.

Common Era / A.D.

Syriac, a descendant of Aramaic used in the northern Levant and Mesopotamia, rose to importance as a literary language of early Christianity in the 3rd to 5th centuries and continued into the early Islamic era.

With the emergence of Islam in the 7th century, the ascendancy of Aramaic was dealt a fatal blow by the Arab conquests, which made another Semitic language — Arabic — the official language of an empire stretching from Spain to Central Asia.

With the patronage of the caliphs and the prestige of its liturgical status, it rapidly became one of the world's main literary languages. Its spread among the masses took much longer; however, as the native populations outside the Arabian Peninsula gradually abandoned their languages in favor of Arabic. As Bedouin tribes settled in conquered areas, it became the main language of not only central Arabia, but also Yemen,[11] the Fertile Crescent, and Egypt. Most of the Maghreb (Northwest Africa) followed, particularly in the wake of the Banu Hilal's incursion in the 11th century, and Arabic became the native language of many inhabitants of Spain. After the collapse of the Nubian kingdom of Dongola in the 14th century, Arabic began to spread south of Egypt; soon after, the Beni Ḥassān brought Arabization to Mauritania.

Meanwhile, Semitic languages were diversifying in Ethiopia and Eritrea, where, under heavy Cushitic influence, they split into a number of languages, including Amharic and Tigrinya. With the expansion of Ethiopia under the Solomonic dynasty, Amharic, previously a minor local language, spread throughout much of the country, replacing languages both Semitic (such as Gafat) and non-Semitic (such as Weyto), and replacing Ge'ez as the principal literary language (though Ge'ez remains the liturgical language for Christians in the region); this spread continues to this day, with Qimant set to disappear in another generation.

Present situation

Arabic is the native language of majorities from Mauritania to Oman, and from Iraq to the Sudan. As the language of the Qur'an and as a lingua franca, it is studied widely in the non-Arabic-speaking Muslim world as well. Its spoken form is divided into a number of varieties, some not mutually comprehensible, united by a single written form. The principal exception to this almost universal use of Arabic script is the Maltese language, genetically a descendant of the extinct Sicilian Arabic dialect. The Maltese alphabet is based on the Roman alphabet with the addition of some letters with diacritic marks and digraphs. Maltese is the only Semitic official language within the European Union.

Despite the ascendancy of Arabic in the Middle East, other Semitic languages still exist. Hebrew, long extinct as a colloquial language and in use only in Jewish literary, intellectual, and liturgical activity, was revived in spoken form at the end of the 19th century by the Jewish linguist Eliezer Ben-Yehuda. It has become the main language of Israel, while remaining the language of liturgy and religious scholarship of Jews worldwide.

Several small ethnic groups, in particular the Assyrians, continue to speak Aramaic dialects (especially Neo-Aramaic, descended from Syriac) in the mountains of northern Iraq, eastern Turkey, northwestern Iran, and northeast Syria, while Syriac itself, a descendant of Old Aramaic, is used liturgically by Lebanese (the Maronites), Syrian and Iraqi Christians.

In Arabic-dominated Yemen and Oman, on the southern rim of the Arabian Peninsula, a few tribes continue to speak Modern South Arabian languages such as Mahri and Soqotri. These languages differ greatly from both the surrounding Arabic dialects and from the (unrelated but previously thought to be related) languages of the Old South Arabian inscriptions.

Historically linked to the peninsular homeland of the Old South Arabian languages, Ethiopia and Eritrea contain a substantial number of Semitic languages; the most widely spoken are Amharic in Ethiopia, Tigre in Eritrea, and Tigrinya in both. Respectively, Amharic and Tigrinya are official languages of Ethiopia and Eritrea. Tigre is spoken by over one million people in the northern and central Eritrean lowlands and parts of eastern Sudan. A number of Gurage languages are spoken by populations in the semi-mountainous region of southwest Ethiopia, while Harari is restricted to the city of Harar. Ge'ez remains the liturgical language for certain groups of Christians in Ethiopia and in Eritrea.

Grammar

The Semitic languages share a number of grammatical features, although variation has naturally occurred – even within the same language as it evolved through time, such as Arabic from the 6th century AD to the present.

Word order

The reconstructed default word order in Proto-Semitic is Verb Subject Object (VSO), possessed–possessor (NG), and noun–adjective (NA). In Classical and Modern Standard Arabic, this is still the dominant order: ra'ā muħammadun farīdan. (lit. saw Muhammad Farid, Muhammad saw Farid). However, VSO has given way in most modern Semitic languages to typologically more common orders (e.g. SVO); for example, the classical order VSO has given way to SVO in most Arabic vernaculars, Maltese, and Hebrew (the latter due to Europeanisation). Modern Ethiopian Semitic languages are SOV, possessor–possessed, and adjective–noun, probably due to Cushitic influence; however, the oldest attested Ethiopian Semitic language, Ge'ez, was VSO, possessed–possessor, and noun–adjective [2]. Akkadian was also predominantly SOV.

Cases in nouns and adjectives

The proto-Semitic three-case system (nominative, accusative and genitive) with differing vowel endings (-u, -a -i); fully preserved in Qur'anic Arabic (see ʾIʿrab), Akkadian and Ugaritic; has disappeared everywhere in the many colloquial forms of Semitic languages, although Modern Standard Arabic maintains such case endings in literary and broadcasting contexts. An accusative ending -n is preserved in Ethiopian Semitic.[12] Additionally, Semitic nouns and adjectives had a category of state, the indefinite state being expressed by nunation.

Number in nouns

Semitic languages originally had three grammatical numbers: singular, dual, and plural. The dual continues to be used in contemporary dialects of Arabic, as in the name for the nation of Bahrain (baħr "sea" + -ayn "two"), and sporadically in Hebrew (šana means "one year", šnatayim means "two years", and šanim means "years"), and in Maltese (sena means "one year", sentejn means "two years", and snin means "years"). The curious phenomenon of broken plurals – e.g. in Arabic, sadd "one dam" vs. sudūd "dams" – found most profusely in the languages of Arabia and Ethiopia, and still common in Maltese, may be partly of proto-Semitic origin, and partly elaborated from simpler origins.

Verb aspect and tense

The aspect systems of West and East Semitic differ substantially; Akkadian preserves a number of features generally attributed to Afroasiatic, such as gemination indicating the imperfect, while a stative form, still maintained in Akkadian, became a new perfect in West Semitic. Proto-West Semitic maintained two main verb aspects: perfect for completed action (with pronominal suffixes) and imperfect for uncompleted action (with pronominal prefixes and suffixes). In the extreme case of Neo-Aramaic, however, even the verb conjugations have been entirely reworked under Iranian influence.

Morphology: triliteral roots

All Semitic languages exhibit a unique pattern of stems consisting typically of "triliteral", or 3-consonant consonantal roots (2- and 4-consonant roots also exist), from which nouns, adjectives, and verbs are formed in various ways: e.g. by inserting vowels, doubling consonants, lengthening vowels, and/or adding prefixes, suffixes, or infixes.

For instance, the root k-t-b, (dealing with "writing" generally) yields in Arabic:

- kataba كَتَبَ or كتب "he wrote" (masculine)

- katabat كَتَبَت or كتبت "she wrote" (feminine)

- katabtu كَتَبْتُ or كتبت "I wrote" (f and m)

- kutiba كُتِبَ or كتب "it was written" (masculine)

- kutibat كُتِبَت or كتبت "it was written" (feminine)

- katabū كَتَبوا or كتبوا "they wrote" (masculine)

- katabna كَتَبنَ or كتبن "they wrote" (feminine)

- katabnā كَتَبْنا or كتبنا "we wrote" (f and m)

- yaktub(u) يَكتُب or يكتب "he writes" (masculine)

- taktub(u) تَكتُب or تكتب "she writes" (feminine)

- naktub(u) نَكتُب or نكتب "we write" (f and m)

- aktub(u) أَكتُب or أكتب "I write" (f and m)

- yuktab(u) يُكتَب or يكتب "being written" (masculine)

- tuktab(u) تُكتَب or تكتب "being written" (feminine)

- yaktubūn(a) يَكتبونَ or يكتبون "they write" (masculine)

- yaktubna يَكتُبنَ or يكتبن "they write" (feminine)

- taktubna تَكتُبنَ or تكتبن "they write" (feminine)

- yaktubān(i) يَكتُبانِ or يكتبان "they both write" (masculine) (for 2 males)

- taktubān(i) تَكتُبانِ or تكتبان "they both write" (feminine) (for 2 females)

- kātaba or "he exchanged letters (with sth.)"

- yukātib(u) "he exchanges (with sth)"

- yatakātabūn(a) يَتَكَتَبونَ or يتكاكتبون "they write to each other" (masculine)

- iktataba اِكتَتَبَ or اكتتب "he is registered" (intransitive) or "he contributed (a money quantity to sth.)" (ditransitive) (the first t is part of a particular verbal transfix, not part of the root)

- istaktaba اِستَكتَبَ or استكتب "to dictate (sth.)"

- kitāb- كِتاب or كتاب "book" (the hyphen shows end of stem before various case endings)

- kutub- كُتُب or كتب "books" (plural)

- kutayyib- كُتَيّْب or كتيب "booklet" (diminutive)

- kitābat- كِتابة or كتابة "writing"

- kātib- كاتِب or كاتب "writer" (masculine)

- kātibat- كاتِبة or كاتبة "writer" (feminine)

- kātibūn(a) كاتِبونَ or كاتبون "writers" (masculine)

- kātibāt- كاتِبات or كاتبات "writers" (feminine)

- kuttāb- كُتاب or كتاب "writers" (broken plural)

- katabat- كَتَبَة or كتبة "writers" (broken plural)

- maktab- مَكتَب or مكتب "desk" or "office"

- makātib- مَكاتِب or مكاتب "desks" or "offices"

- maktabat- مَكتَبة or مكتبة "library" or "bookshop"

- maktūb- مَكتوب or مكتوب "written" (participle) or "postal letter" (noun)

- katībat- كَتيبة or كتيبة "squadron" or "document"

- katā’ib- كَتائِب or كتائب "squadrons" or "documents"

- iktitāb- اِكتِتاب or اكتتاب "registration" or "contribution of funds"

- muktatib- مُكتَتِب or مكتتب "subscription"

- istiktāb- اِستِكتاب or استكتاب "dictation"

and the same root in Hebrew (where it appears as k-t-ḇ):

- kataḇti כתבתי "I wrote"

- kataḇta כתבת "you (m) wrote"

- kataḇ כתב "he wrote"

- kattaḇ כתב "reporter" (m)

- katteḇet כתבת "reporter" (f)

- kattaḇa כתבה "article" (plural kataḇot כתבות)

- miḵtaḇ מכתב "postal letter" (plural miḵtaḇim מכתבים)

- miḵtaḇa מכתבה "writing desk" (plural miḵtaḇot מכתבות)

- ktoḇet כתובת "address" (plural ktoḇot כתובות)

- ktaḇ כתב "handwriting"

- katuḇ כתוב "written" (f ktuḇa כתובה)

- hiḵtiḇ הכתיב "he dictated" (f hiḵtiḇa הכתיבה)

- hitkatteḇ התכתב "he corresponded (f hitkatḇa התכתבה)

- niḵtaḇ נכתב "it was written" (m)

- niḵteḇa נכתבה "it was written" (f)

- ktiḇ כתיב "spelling" (m)

- taḵtiḇ תכתיב "prescript" (m)

- meḵuttaḇ מכותב "addressee" (meḵutteḇet מכותבת f)

- ktubba כתובה "ketubah (a Jewish marriage contract)" (f) (note: b here, not ḇ)

also appearing in Maltese, where consonantal roots are referred to as the għerq:

- jiena ktibt "I wrote"

- inti ktibt "you wrote" (m or f)

- huwa kiteb "he wrote"

- hija kitbet "she wrote"

- aħna ktibna "we wrote"

- intkom ktibtu "you (pl) wrote"

- huma kitbu "they wrote"

- huwa miktub "it is written"

- kittieb "writer"

- kittieba "writers"

- kitba "writing"

- ktib "writing"

- ktieb "book"

- kotba "books"

- ktejjeb "booklet"

In Tigrinya and Amharic, this root survives only in the noun kitab, meaning "amulet", and the verb "to vaccinate". Ethiopic-derived languages use a completely different root (ṣ-ḥ-f) for the verb "to write" (this root exists in Arabic and is used to form words with close meaning to "writing", such as ṣaḥāfa "journalism", and ṣaḥīfa "newspaper" or "parchment").

Verbs in other non-Semitic Afroasiatic languages show similar radical patterns, but more usually with biconsonantal roots; e.g. Kabyle afeg means "fly!", while affug means "flight", and yufeg means "he flew" (compare with Hebrew, where hafleg means "set sail!", haflaga means "a sailing trip", and heflig means "he sailed", while the unrelated uf, te'ufah and af pertain to flight).

Common vocabulary

Due to the Semitic languages' common origin, they share many words and roots. For example:

| English | Proto-Semitic | Akkadian | Arabic | Aramaic | Hebrew | Ge'ez | Mehri |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| father | *ʼab- | ab- | ʼab- | ʼaḇ-āʼ | ʼāḇ | ʼab | ḥa-yb |

| heart | *lib(a)b- | libb- | lubb- | lebb-āʼ | lēḇ(āḇ) | libb | ḥa-wbēb |

| house | *bayt- | bītu, bētu | bayt- | bayt-āʼ | báyiṯ, bêṯ | bet | beyt, bêt |

| peace | *šalām- | šalām- | salām- | šlām-āʼ | šālôm | salām | səlōm |

| tongue | *lišān-/*lašān- | lišān- | lisān- | leššān-āʼ | lāšôn | lissān | əwšēn |

| water | *may-/*māy- | mû (root *mā-/*māy-) | māʼ-/māy | mayy-āʼ | máyim | māy | ḥə-mō |

Sometimes certain roots differ in meaning from one Semitic language to another. For example, the root b-y-ḍ in Arabic has the meaning of "white" as well as "egg", whereas in Hebrew it only means "egg". The root l-b-n means "milk" in Arabic, but the color "white" in Hebrew. The root l-ḥ-m means "meat" in Arabic, but "bread" in Hebrew and "cow" in Ethiopian Semitic languages; the original meaning was most probably "food". The word medina (root: m-d-n) has the meaning of "metropolis" in Amharic and "city" in Arabic and Hebrew, but in Modern Hebrew it is usually used as "state".

Of course, there is sometimes no relation between the roots. For example, "knowledge" is represented in Hebrew by the root y-d-ʿ but in Arabic by the roots ʿ-r-f and ʿ-l-m and in Ethiosemitic by the roots ʿ-w-q and f-l-ṭ.

Classification

The classification given below, based on shared innovations – established by Robert Hetzron in 1976 with later emendations by John Huehnergard and Rodgers as summarized in Hetzron 1997 – is the most widely accepted today, but is still disputed. In particular, several Semiticists still argue for the traditional view of Arabic as part of South Semitic, and a few (e.g. Alexander Militarev or the German-Egyptian professor Arafa Hussein Mustafa) see the South Arabian languages as a third branch of Semitic alongside East and West Semitic, rather than as a subgroup of South Semitic. Roger Blench notes that the Gurage languages are highly divergent and wonders whether they might not be a primary branch, reflecting an origin of Afroasiatic in or near Ethiopia. At a lower level, there is still no general agreement on where to draw the line between "languages" and "dialects" – an issue particularly relevant in Arabic, Aramaic, and Gurage below – and the strong mutual influences between Arabic dialects render a genetic subclassification of them particularly difficult.

The traditional grouping of the Semitic languages (prior to the 1970s), based partly on non-linguistic data, differs in several respects; in particular, Arabic was put in South Semitic, and Eblaite had not been discovered at that time.

East Semitic languages

- Akkadian — extinct

- Eblaite — extinct

West Semitic languages

Northwest Semitic languages

- Amorite — extinct

- Ugaritic — extinct

- Canaanite languages

- Ammonite — extinct

- Moabite — extinct

- Edomite — extinct

- Hebrew

- Biblical Hebrew — Used in the study and public reading of the Torah.

- Standard, Early or Judahite Biblical Hebrew

- Late Biblical Hebrew or Israelian Hebrew (intermediate with Mishnaic Hebrew)

- Mishnaic Hebrew — Used in the study of the Talmud and other Rabbinic writings. Lingua franca (along with Aramaic) of Rabbis in the Middle Ages.

- Medieval Hebrew — Developed into Modern Hebrew.

- Samaritan Hebrew — Used by the Samaritans in Holon, Tel Aviv and Nablus.

- Ashkenazi Hebrew — live descendants

- Teimani Hebrew — Spoken mainly by Yemenite Jews.

- Sephardi Hebrew — Major basis of modern pronunciation.

- Modern Hebrew — Spoken mostly in Israel.

- Mizrahi Hebrew — Modern Hebrew with accent influence of Sephardi and Teimani Hebrew - Spoken in Israel, Yemen, Iraq, Puerto Rico, New York etc.

- Biblical Hebrew — Used in the study and public reading of the Torah.

- Phoenician — extinct

- Punic — extinct

- Aramaic languages

- Western Aramaic languages

- Nabataean — extinct

- Western Middle Aramaic languages

- Jewish Middle Palestinian Aramaic — extinct

- Samaritan Aramaic — live descendants

- Christian Palestinian Aramaic — extinct

- Western Neo-Aramaic — live descendants

- Eastern Aramaic languages

- Biblical Aramaic — extinct

- Hatran Aramaic — extinct

- Syriac — live descendants

- Jewish Middle Babylonian Aramaic — extinct

- Chaldean Neo-Aramaic — live descendants

- Assyrian Neo-Aramaic — live descendants

- Senaya — live descendants

- Koy Sanjaq Surat — live descendants

- Hertevin — live descendants

- Turoyo — live descendants

- Mlahso — extinct

- Mandaic — live descendants

- Judaeo-Aramaic — live descendants

- Western Aramaic languages

Arabic languages

- Ancient North Arabian — extinct

- Arabic

- Fus'ha — (اللغة العربية الفصحى literally "eloquent"), the written language, divided by specialists into:

- Classical Arabic — the language of the Qur'an and early Islamic Arabic literature,

- Middle Arabic — a generic term for premodern post-classical efforts to write Classical Arabic, characterized by frequent hypercorrections and occasional lapses into more colloquial usage. Not a spoken language.

- Modern Standard Arabic — modern literary (non-native) language used in formal media and written communication throughout the Arab World, differing from Classical Arabic mainly in numerous neologisms for concepts not found in medieval times, as well as in occasional calques on idioms from Western languages.

- Fus'ha — (اللغة العربية الفصحى literally "eloquent"), the written language, divided by specialists into:

- Numerous Modern Arabic spoken dialects — roughly divided by the Ethnologue into:

- Eastern Arabic dialects

- Arabian Peninsular dialects

- Dhofari Arabic — Oman/Yemen

- Hadrami Arabic — Yemen

- Hejazi Arabic — Saudi Arabia

- Najdi Arabic — Saudi Arabia

- Omani Arabic

- Sana'ani Arabic — Yemen

- Ta'izzi-Adeni Arabic — Yemen

- Judeo-Yemeni Arabic

- Bedouin/Bedawi Arabic dialects

- Eastern Egyptian Bedawi Arabic

- Peninsular Bedawi Arabic — Arabian Peninsula

- Central Asian dialects

- Central Asian Arabic

- Khuzestani Arabic

- Shirvani Arabic— extinct

- Egyptian Arabic dialects — Egypt, Palestinian territories

- Sa'idi Arabic — Upper Egypt

- Gulf Arabic dialects — includes speakers in Iran

- Bahrani Arabic — Bahrain

- Gulf Arabic — Persian Gulf (all bordering countries)

- Shihhi Arabic — United Arab Emirates

- Levantine Arabic dialects

- Cypriot Maronite Arabic

- North Levantine Spoken — Lebanon, Syria

- Lebanese Arabic

- South Levantine Spoken — Jordan, Palestinian territories, Israel

- Palestinian Arabic

- Iraqi Arabic — Iraq

- Judeo-Iraqi Arabic

- Sudanese Arabic

- Arabian Peninsular dialects

- Maghrebi Arabic dialects

- Algerian Arabic

- Saharan Arabic

- Shuwa Arabic — Chad

- Hassānīya Arabic — Mauritania and Saharan area

- Libyan Arabic

- Judeo-Tripolitanian Arabic — Libyan dialect

- Andalusian Arabic Old Iberian Arabic — extinct

- Siculo-Arabic — Sicily, extinct

- Maltese language — a genetic descendant of the extinct Siculo-Arabic variety.

- Moroccan Arabic

- Judeo-Moroccan Arabic

- Tunisian Arabic

- Judeo-Tunisian Arabic

- Eastern Arabic dialects

Several Jewish dialects, typically with a number of Hebrew loanwords, are grouped together with classical Arabic written in Hebrew script under the imprecise term Judeo-Arabic.

South Semitic languages

Western South Semitic languages

- Old South Arabian — extinct, formerly believed to be the linguistic ancestors of modern South Arabian and Ethiopian Semitic languages (for which see below)

- Sabaean — extinct

- Minaean — extinct

- Qatabanian — extinct

- Hadhramautic — extinct

- Ethiopic languages (Ethio-Semitic, Ethiopian Semitic):

- North

- Ge'ez (Ethiopic) — extinct, liturgical use in the Ethiopian Orthodox Tewahedo and Eritrean Orthodox Tewahedo Churches

- Tigrinya — national language of Eritrea

- Tigré

- Dahlik language — "newly discovered"

- South

- Transversal

- Amharic-Argobba

- Amharic — national language of Ethiopia

- Argobba

- Harari-East Gurage

- Harari

- East Gurage

- Selti (also spelled Silt'e)

- Zway (also called Zay)

- Ulbare

- Wolane

- Inneqor

- Outer

- n-group:

- Gafat — extinct

- Soddo (also called Kistane)

- Goggot

- tt-group:

- Mesmes — extinct

- Muher

- West Gurage

- Masqan (also spelled Mesqan)

- CPWG

- Central Western Gurage:

- Ezha

- Chaha

- Gura

- Gumer

- Peripheral Western Gurage:

- Gyeto

- Ennemor (also called Inor)

- Endegen

- Central Western Gurage:

- CPWG

- Masqan (also spelled Mesqan)

- n-group:

- Amharic-Argobba

- Transversal

- North

Eastern South Semitic languages

These languages are spoken in the Arabian peninsula, in Yemen and Oman.

- Bathari

- Harsusi

- Hobyot

- Jibbali (also called Shehri)

- Mehri

- Soqotri — on the islands of Socotra, Abd el Kuri and Samhah (Yemen) and in the UAE.

Living Semitic languages by number of speakers

| lang | speakers |

|---|---|

| Arabic | 206,000,000[13] |

| Amharic | 27,000,000 |

| Tigrinya | 6,700,000 |

| Hebrew | 5,000,000[6] |

| Syriac Aramaic | 2,105,000 |

| Silt'e | 830,000 |

| Tigre | 800,000 |

| Sebat Bet Gurage | 440,000 |

| Maltese | 371,900[14] |

| Modern South Arabian languages | 360,000 |

| Inor | 280,000 |

| Soddo | 250,000 |

| Harari | 21,283 |

See also

- Proto-Semitic language

- Proto-Canaanite alphabet

- Middle Bronze Age alphabets

Notes

- ↑ Including all varieties.

- ↑ Ethnologue report for language code:arb

- ↑ 1994 Ethiopian census

- ↑ Amharic alphabet, pronunciation and language

- ↑ Ethnologue report for language code:tir

- ↑ 6.0 6.1 Gordon, Raymond G., Jr. (ed.), 2005. Ethnologue: Languages of the World, Fifteenth edition. Dallas, Tex.: SIL International. Online version: http://www.ethnologue.com/. (Hebrew->Population total all countries, [1])

- ↑ The Origins of Afroasiatic – Ehret et al. 306 (5702): 1680c – Science

- ↑ McCall, Daniel F. (1998). "The Afroasiatic Language Phylum: African in Origin, or Asian?". Current Anthropology 39 (1): 139–44. doi:10.1086/204702. http://links.jstor.org/sici?sici=0011-3204%28199802%2939%3A1%3C139%3ATALPAI%3E2.0.CO%3B2-J&size=LARGE..

- ↑ Hayward 2000; http://www.sciencemag.org/cgi/content/full/306/5702/1680c

- ↑ Kitchen A, Ehret C, Assefa S, Mulligan CJ. (2009). Bayesian phylogenetic analysis of Semitic languages identifies an Early Bronze Age origin of Semitic in the Near East. Proc Biol Sci. 276(1668):2703-10. doi:10.1098/rspb.2009.0408 PMID 19403539 supplementary material.

- ↑ Nebes, Norbert, "Epigraphic South Arabian," in von Uhlig, Siegbert, Encyclopaedia Aethiopica (Wiesbaden: Harrassowitz Verlag, 2005), pps.335.

- ↑ Moscati, Sabatino (1958). "On Semitic Case-Endings". Journal of Near Eastern Studies 17 (2): 142–43. doi:10.1086/371454. "In the historically attested Semitic languages, the endings of the singular noun-flexions survive, as is well known, only partially: in Akkadian and Arabic and Ugaritic and, limited to the accusative, in Ethiopic.

- ↑ Ethnologue: "206,000,000 L1 speakers of all Arabic varieties"

- ↑ Ethnologue report for Maltese, retrieved 2008-10-28

References

- Patrick R. Bennett. Comparative Semitic Linguistics: A Manual. Eisenbrauns 1998. ISBN 1-57506-021-3.

- Gotthelf Bergsträsser, Introduction to the Semitic Languages: Text Specimens and Grammatical Sketches. Translated by Peter T. Daniels. Winona Lake, Ind. : Eisenbrauns 1995. ISBN 0-931464-10-2.

- Giovanni Garbini. Le lingue semitiche: studi di storia linguistica. Istituto Orientale: Napoli 1984.

- Giovanni Garbini & Olivier Durand. Introduzione alle lingue semitiche. Paideia: Brescia 1995.

- Robert Hetzron (ed.) The Semitic Languages. Routledge: London 1997. ISBN 0-415-05767-1. (For family tree, see p. 7).

- Edward Lipinski. Semitic Languages: Outlines of a Comparative Grammar. 2nd ed., Orientalia Lovanensia Analecta: Leuven 2001. ISBN 90-429-0815-7

- Sabatino Moscati. An introduction to the comparative grammar of the Semitic languages: phonology and morphology. Harrassowitz: Wiesbaden 1969.

- Edward Ullendorff, The Semitic languages of Ethiopia: a comparative phonology. London, Taylor's (Foreign) Press 1955.

- William Wright & William Robertson Smith. Lectures on the comparative grammar of the Semitic languages. Cambridge University Press 1890. [2002 edition: ISBN 1-931956-12-X]

- Arafa Hussein Mustafa. "Analytical study of phrases and sentences in epic texts of Ugarit." (German title: Untersuchungen zu Satztypen in den epischen Texten von Ugarit). PhD-Thesis. Martin-Luther-University Halle-Wittenberg, Germany: 1974.

External links

- Chart of the Semitic Family Tree American Heritage Dictionary (4th ed.)

- Semitic genealogical tree (as well as the Afroasiatic one), presented by Alexander Militarev at his talk “Genealogical classification of Afro-Asiatic languages according to the latest data” (at the conference on the 70th anniversary of Vladislav Illich-Svitych, Moscow, 2004; short annotations of the talks given there(Russian))

- "Semitic" in SIL's Ethnologue

- Ancient snake spell in Egyptian pyramid may be oldest Semitic inscription

|

|||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||